The History Begins in 1762

The history of Olofsfors dates back to 1762, during the era when Europe was industrializing. Quality already brought pride to the blacksmiths and the ironworks in Olofsfors at that time.

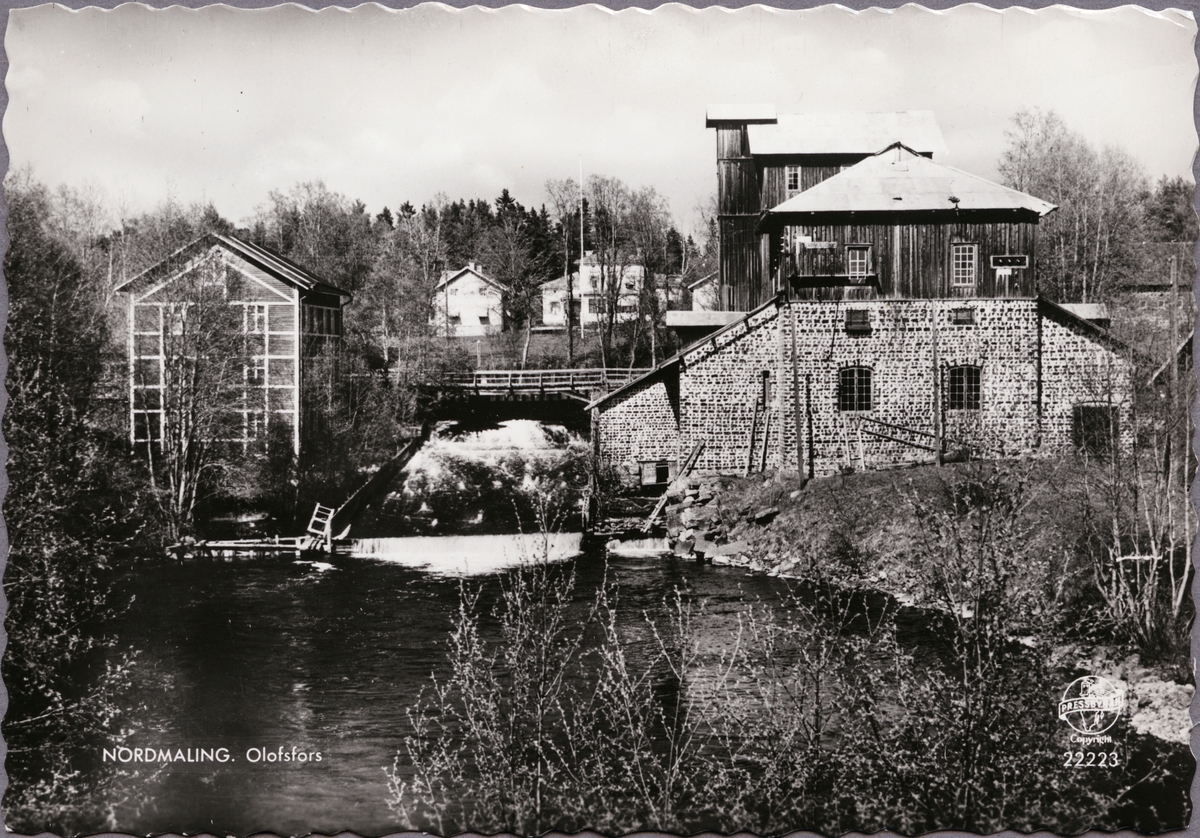

Businessman John Jennings, together with his partner Robert Finlay, established a mill in 1758 at the mouth of the Rickle River north of Umeå. The mill was named Robertsfors after its founder. It was likely while traveling from Robertsfors that Jennings passed the Ledu River and saw the site where Olofsfors Mill stands today. The location offered the desired forest, proximity to the sea, and several rapids for harnessing waterpower.

The iron industry was heavily regulated in those years, and it wasn’t until 1762 that Jennings received his permits. The mill faced tough early years with disputes and competition over land. The plan was for the local people to supply charcoal to the mill. However, farmers were reluctant to abandon the more profitable tar production for the demanding and taxing art of charcoal making. The deforestation that came with charcoal production worried both the townspeople in Umeå and Härnösand and the farmers already living in the area.

In 1769, the farmers attempted to ban the mill’s operations in parliament. The following year, parliament rejected the complaints. Iron export was deemed so important that, in addition to the forest, the mill was granted tax exemption for its first nine years—a benefit it retained for 37 years.

John Jennings – In 1762, John received the permits needed to create his ironworks despite farmers’ protests.

New Owner and New Challenges

The man who succeeded Jennings was Johan Christoffer Pauli. Pauli managed to reverse the company’s financial decline but was not well-liked by his employees or the local community. People simply didn’t want to work for him. Pauli’s final years as mill owner in Olofsfors were difficult. Extensive repairs on a flooded blast furnace, the loss of tax breaks, and significant investments in new technology were costly, but the mill was ready to produce more iron than ever before. Then came the Russians.

The year was 1809, and just a few miles north of the mill, the bloody Finnish War raged. Many men from the mill and surrounding areas were conscripted. Charcoal deliveries were severely reduced, and heavy tax increases to fund the war crushed the mill’s optimism. To keep the business afloat, Pauli had to sell several of his privileges to other mills. Three years before his death in 1823, Pauli transferred the mill to his children. Once again, the people of Olofsfors held their breath. After failing to sell the mill, the decision was made to reinvest heavily. Thanks to the eldest son, Johan August Pauli, a prosperous future awaited Olofsfors Mill. Construction surged, and forging was more active than ever. By the mid-1800s, the sawmill industry became increasingly important, and by 1846, wood accounted for 46% of the mill’s revenue.

Technological Development Changes the Industry

The mill now faced new challenges. Sweden continued to export iron, but technological advancements, particularly methods to reduce dependence on charcoal, meant that mills no longer needed to be located near large forests. Transporting ore to and iron from northern Sweden was no longer profitable. Iron production became centralized, and between 1860 and 1900, the number of Swedish ironworks halved. Eventually, only the major mills in southern Sweden remained.

Olofsfors Mill not only struggled to compete with its iron but also faced additional competition. In 1849, Sweden’s first steam sawmill was established outside Sundsvall. It wasn’t long before forward-thinking traders from Nordmaling began scouting locations to build their own steam sawmill. In 1863, a sawmill was established in Rundvik. Ownership of Olofsfors Mill had become fragmented after the Pauli family’s involvement ended. The mill encompassed nearly 15,000 hectares of forest, making it clear why the newly established Nordmalings Ångsåg AB (NÅAB) gradually acquired shares in the mill to gain access to its valuable forest resources.

By 1886, NÅAB owned the entire Olofsfors Mill. During this period, the mill had been modernized, and new technology made the blast furnace and forges more efficient and productive than ever before. Even under NÅAB’s ownership, the focus remained on blast furnace operations. The charcoal issue had been partially resolved by using by-products from the steam sawmill. However, despite the blast furnace producing more pig iron than ever, it was no longer profitable.

The Blast Furnace Goes Out – After 56,740 Tons of Pig Iron

n 1894, the blast furnace went cold, but this did not mark the end of iron production at Olofsfors. The production of bar iron and manufactured iron continued, with pig iron now being shipped to the mill. The hammer forges in Klöse and Holmfors had already been shut down, and forging was concentrated in Olofsfors. Most of the forged iron was used internally by the company.

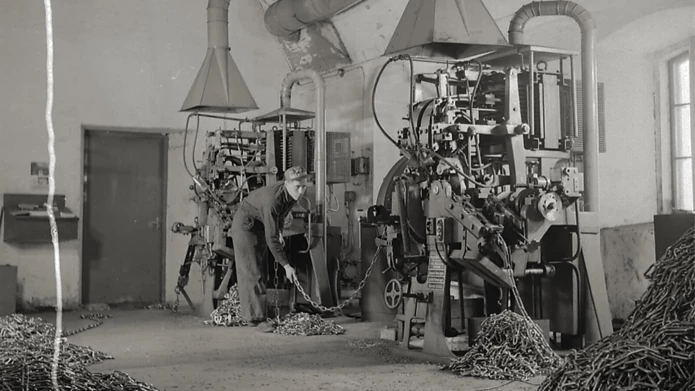

One product in particular demand for timber floating was chains, which led to the establishment of a chain forge next to the bar iron hammer. Additionally, woodworking items like wagon wheels and timber tools were important products for the mill during this period.

In the 1950s, chain production was moved to modern facilities in the southern part of the barn. However, demand for chains declined as timber floating became obsolete, with timber increasingly transported by truck. This necessitated quick adaptability. The solution came in the form of contract manufacturing for forest machine components. One client was System Svedlund, which in 1976 acquired the company. As a result, the entire production of forest machine tracks was moved to Olofsfors. The next major product categories to be developed were road steel and bucket steel.

The chains were still needed for timber floating – It was grueling and strenuous work in the chain forge, which at the time was housed in the western part of the barn.

Back to the Wikström Family

At this time, the company was a subsidiary of Masonite AB but was repurchased in 1982 by the Wikström family, who had been the primary stakeholders in the mill for most of the 20th century. In 1991, Olofsfors AB moved to new premises adjacent to the mill area, and in 1999, entirely new facilities for wear steel and a new office building were added. Between 2002 and 2004, an evaluation was conducted to consider relocating production to another site, but ultimately, a strategic decision was made to keep production in Olofsfors. The company invested in a fully automated production line.

It fell to the women to handle the home, household, and the children’s upbringing. The blacksmiths’ rights included access to a cowshed and fodder for two cows, whose care was the woman’s responsibility. Additionally, women were responsible for sowing and harvesting the family’s garden plot. On top of this, they had to perform the labor duties they were obligated to fulfill. The laundry house was probably the only place where women had the opportunity to meet.

The wives of furnace and forge workers had similar responsibilities to sailors’ wives. They had to manage the household, care for children, and oversee the small-scale farming that most families maintained.

Children at the Mill

Children were quickly introduced to adult life. At confirmation, they were considered old enough to perform daily labor. Childhood was characterized by everyday tasks such as carrying firewood and water and looking after younger siblings. However, as long as one knew their place, the adult world was open to the children’s curious eyes. There was the furnace with its roaring machines, the forge with its pounding hammers, and the manor house with its unfamiliar way of life.

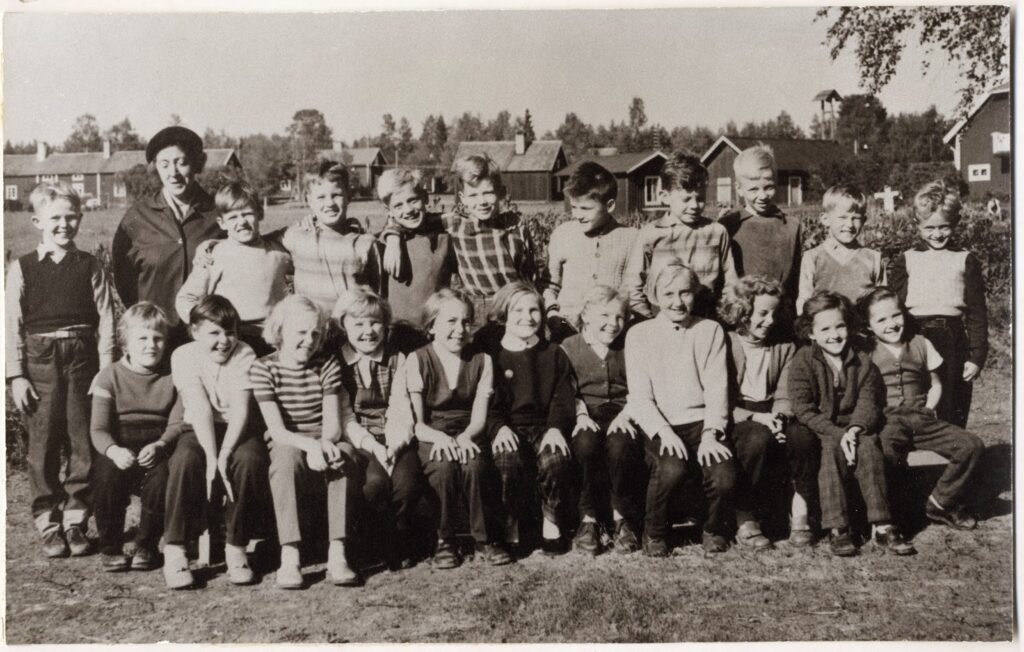

The first school in Olofsfors was built in 1831. Mill and sawmill communities were early adopters of schools, while general compulsory schooling wasn’t introduced until 1842.

Workers’ wages were issued in the form of store credits, as cash transactions were rare. It was not uncommon for workers to fall into debt to the mill, thereby losing their independence. Children inherited both their parents’ professions and their debts.

School Class Grade 3, 1956 –

Back row from left: Kennet Sjöström, teacher Inga Öberg, Leif Salmgren, Kennet Holmlund, Lars Gustafsson, Ulf Lundberg, Rolf Fjällman, Roger Berggren, Hans Wallander, Björn Anklert, Åke Liljedahl. Seated from left: Elinore Ersholt, GunMarie Wikman, Jeanette Juneblad, Birgith Wäringstam, Margareta Landström, Ann Sofie Söderström, Marianne Söderström, Inga Öberg, Barbro Öberg, Gunilla, and Siv Norberg.